Biography

Born in Bombay, India on January 20, 1959, to a family that had migrated to the west-coast metropolis from

Kathiawar in Gujarat, Atul Dodiya is one of India’s most acclaimed postcolonial artist who refuses to confine

himself to a box neatly labelled with a national identity; his location in India serves him as a base from which

to intervene in a variety of cultural and political histories to which the postcolonial self is heir.

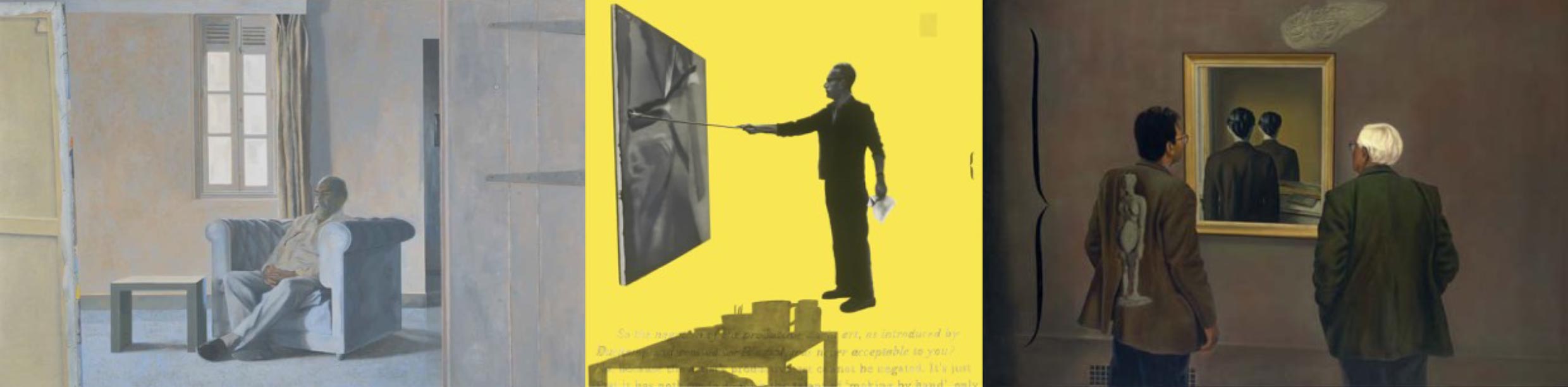

Dodiya’s paintings, assemblages and sculpture-installations embody a passionate, sophisticated response to

the sense of crisis he feels, as an artist and as a citizen, in a transitional society damaged by the continuing

asymmetries of capital yet enthused by the transformative energies of globalization. When Dodiya was ten, he

suffered an injury to the eye while playing with friends in a century-old village-like neighborhood of DK Wadi

in Bombay. That same year, he felt in his bones the absolute conviction that he wanted to be an artist. For

the next twenty-five years, he would be plagued by the artist’s worst nightmare: the fear of impending

blindness. Regardless of this, he embraced the life of the studio, committing himself to the edge of severe

visual impairment, a condition eventually and permanently remedied by surgery. But by the mid-1990s,

Dodiya’s voracious desire to record a diverse range of experiences by painterly means had already made him a

front-runner of his generation of post-colonial Indian artists. A number of paintings that date to this early

phase of his career attest to this potentially destabilizing yet dynamically productive tension in his

consciousness. Like many of his contemporaries, Dodiya enacted a radical departure from the modernist

dogmas of stylistic singularity and medium-specificity; he replaced these with a dazzling and extravagant

multiplicity of styles and a repertoire of media among which he ranges with the zest and adroitness of an

orchestral imagination. In February 2002, a brazenly ascendant Hindu Right wing would orchestrate a

genocide against the Muslim minority in the state of Gujarat, plunging Gujaratis of liberal persuasion, such

as Dodiya, into profound dejection. As one who had long subscribed to Gandhi’s philosophy of compassion,

mutuality and non-violence, Dodiya was especially disturbed by these events that cataclysmically bookend the

decade 1992-2002 of his life which came to inform his art strongly.

Dodiya registered another turning point in 1991-1992, the year he and his wife, the artist Anju Dodiya, spent

largely in Paris on a French Government scholarship: his understanding of his own location as an artist

underwent a radical transformation during this period. At 32 , he was leaving India for the first time; and for

the first time, he would see in actuality, many of the canonical works of art and legendary institutions that had

inspired him as a student and young artist. Shocked with his first encounter with original works by Picasso,

Modigliani and several magisterial figures in the western art scene, he began to reassess the modernist

doctrines in which he had been raised in Bombay, in relation to what he saw to be far more mercurial and

experimental course of the 20th century art. After his return from Paris in 1992, living there for a year and

seeing so much art, Dodiya wanted to change many things in his work. ‘In Paris I overcame my anxieties

about what Tyeb would say, what Akbar would say, what my friends would say. Their opinion still mattered

to me and I took it very seriously, but I knew that I simply had to do what I felt I had to do. I allowed for the

new experiences, expressions. I began to develop a feeling for a different kind of subject matter and came up

with a reshuffled realism”, says Dodiya.

Importantly, through the late 1990s, Dodiya revitalized the painted surface by responding to the challenges

posed by new mediatic structure such as satellite television and the internet on the one hand, and by new

artistic modes such as vide0, assemblage and installation on the other. He began to construct his paintings as

argument, allegories, riddles, or aphorisms. In so re-engineering the machinery of the painting, he brought a

gamut of unpredictable and mutually unrelated energies to bear on pictorial space: his corpus of references

soon grew to include poems, comic strips, traders’ lists of wares, advertising billboards, movie posters,

cinema stills, popular religious oleographs, and streetside graffiti, as well as his favorite paintings from the

postcolonial Indian, Mughal, European and American traditions By 1999, Dodiya’s transformation was

complete. He was far more readily identified with a flamboyantly hybrid idiom in which the distinctions

between classical and demotic, regional and international, beaux arts and popular culture, had not simply

been blurred but actively broken down in the interests of a fictive, sparking, idiosyncratic collage of impulses.

Text Reference:

Excerpts from the book Atul Dodiya published by Vadehra Art Gallery & Prestel in 2013